Osborne House

(vero;2022-May-30)

Osborne House is the site not to be missed when visiting the Isle of Wight. We were there at 10am right at the opening and headed first for the grounds, Swiss Cottage and the Beach. This was a good idea as hardly anybody was around and we had the place nearly for ourselves. We started meeting the unavoidable crowds as we returned to the Palace. We experienced Osborne as a shrine to everything Victorian: room after room, all sorts of memorabilia was on display, with Victoria here, Albert there, and the children in between, and on top of it, an haphazard accumulation of paintings and sculptures from the Royal Collection without any obvious logic to our eyes, it all felt a bit too much. However, we found the room dedicated to Victoria's and Albert's descendance featuring the family trees and links to European monarchies most interesting and we must admit that seeing Victoria's deathbed is quite something. But for us the best came at the end: the great Durbar room and the corridor leading to it, adorned with impressive and realistic paintings representing people from the Empire's Jewel, India; it was the highlight of our day, see the second photo gallery below for Rudolf Swoboda's portraits of Indian people.

Rudolf Swoboda's portraits of Indian people

Rudolf Swoboda sailed for India on 7 October 1886. Queen Victoria paid for his passage and gave him £300 to cover his travelling expenses. In return he was to provide her with sketches worth £300. She gave Swoboda very specific instructions: The Sketches Her Majesty wishes to have are of the various types of the different nationalities. They should consist of heads of the same size as those already done for The Queen, and also small full lengths, as well as sketches of landscapes, buildings, and other scenes. Her Majesty does not want any large pictures done at first, but thinks that perhaps you could bring away material for making them should they eventually be wished for.

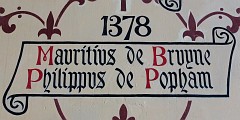

Most of Swoboda's paintings are exposed in the Durbar corridor which leads to the Durbar room. All names and details copied and pasted from the Royal Collection website.

Go back to Portchester Castle or go on to English Heritage: South West England

$updated from: English Heritage Snapshots.htxt Mon 04 Mar 2024 16:04:47 trvl2 (By Vero and Thomas Lauer)$