Jeanne d'Arc

(vero;2020-Dec-15)

Setting the scene

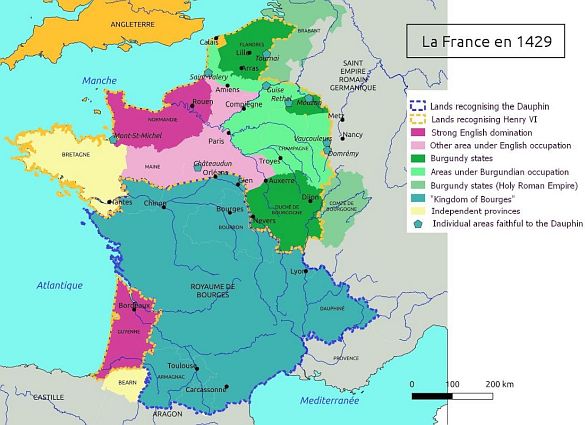

When Jeanne starts her campaign in 1429, France is in the throes of the Hundred Years' War with England (1337-1453) and it does not look good at all for the French king Charles VII as he is facing continuous English claims to his kingdom and fights a civil war against the fraction of Burgundy disputing his right to the French crown. Below are a few dates and historical facts to explain how it came to this sorry state of affairs.

- 1361: the duke of Burgundy Philippe I dies without an heir and his possessions fall to the French king Jean II le Bon who gives them to his fourth son Philippe le Hardi in 1363.

- 1364: Jean II le Bon dies. His son Charles V le Sage becomes king of France. During his reign, Charles V succeeded in recovering almost all the land lost by his predecessors since the beginning of the Hundred Years' War. He restored the authority of the royal power and brought the kingdom out of a difficult period that combined the heavy military defeats of Crécy and Poitiers (1346 and 1356) with the great Black Death of 1347-1351.

- 1380: Charles V dies. His son Charles VI is too young to reign and his uncle the Duke of Burgundy Philippe le Hardi takes over the regency.

- 1388: Charles VI reaches his majority and takes over the reins of the kingdom.

- 1393: Charles VI becomes mad and is unable to govern any further. His wife, the queen Isabeau de Bavière becomes regent under the strong influence of Philippe le Hardi.

- 1404: Philippe le Hardi dies and his son Jean sans Peur is not able to retain his influence over the queen who is now advised by Louis I d'Orléans, brother of the mad king.

- 1407: Jean sans Peur orders the murder of Louis I d'Orléans, sparking a civil war between the so-called Armagnacs (supporters of the king) and the Burgundian party which battles against the king and wins over significant parts of the kingdom in the North-East.

- 1415: Taking advantage of the French turmoil, the English king Henry V restarts hostilities and lands in Normandy. After a resounding victory at the battle of Agincourt which decimates the French chivalry, the English take possession of Normandy.

- 1418: The civil war is still raging and the Burgundian seize Paris, holding the mad king Charles VI in their control. His 15 years old son, the dauphin Charles manages to flee to Bourges where in view of his father's incapacity to reign, he proclaims himself regent of the kingdom of France and tries to organise a resistance against the Burgundian and the English.

- 1419: Jean sans Peur is assassinated by the Armagnacs, an act which fuels the Civil War even further. His son Philippe le Bon escalates the conflict by striking an alliance with England.

- 1420: France and England sign the Treaty of Troyes in which the mad king of France Charles VI, a puppet of the Burgundian recognises the English king Henry V as legitimate heir to his throne.

- 1422: Charles VI dies and the dauphin Charles refutes the Treaty of Troyes and proclaims himself king of France under the name of Charles VII on 30 October in the cathedral of Bourges.

- 1429: Charles VII finds himself the disputed king of a diminished kingdom under attack and after seven years of reign seems far away from being able to legitimate his claim and be crowned king of France in the city of Reims which is held by his enemies.

N.B.: The province of Guyenne (the pink region south of Bordeaux) has been under the dominion of the kings of England since the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II in 1154 and has remained English until the end of the Hundred Years' War.

The epic of Jeanne d'Arc

Jeanne was born in 1412 in Domrémy, a small village in the marshes of Lorraine and came from a fairly well-to-do peasant family. She was a very pious child, illiterate, went to church and gave alms to the poor.

She declared that she heard voices for the first time at the age of thirteen as she was tending sheep in her father's garden. After that, she had repeated visions of Saint Michael, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret ordering her to take the dauphin to Reims to have him crowned and to “drive the English out of France”. Still, she resisted those “voices” for several years and decided to keep quiet at first.

She declared that she heard voices for the first time at the age of thirteen as she was tending sheep in her father's garden. After that, she had repeated visions of Saint Michael, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret ordering her to take the dauphin to Reims to have him crowned and to “drive the English out of France”. Still, she resisted those “voices” for several years and decided to keep quiet at first.

In 1428 the English stormed Lorraine and the village of Domrémy was ransacked and burnt by armed bands, forcing Jeanne and her family to take refuge in the nearby town of Neufchâteau. Back in Domrémy having faced the reality of war and hearing about the siege of Orléans by the English who tried to break into the city to open the route to the region south of the river Loire held by Charles VII, she could not resist any longer. She confided in her uncle and convinced him to escort her to Robert de Baudricourt, representative of the dauphin and captain of Vaucouleurs, the neighbouring fortress of Domrémy: she wanted to ask him for support in her attempt to free France and give her the permission to join the troops of the dauphin and fulfil her destiny. However Baudricourt, believing her to be a bit deranged, sent her back to her parents with a slap in the face.

But Jeanne did not give up. She left Domrémy and settled in Vaucouleurs as a healer. There she acquired a certain notoriety, so much that the sick Duke Charles II of Lorraine gave her a safe-conduct to visit him in Nancy. Once there she promised him that she would pray for his recovery under the condition that he abandoned his mistress and granted her request for an escort to go and free France from the English… As he heard this, impressed by such determination and unsettled by the fact that a prophecy had been circulating for some time that a virgin from the marshes of Lorraine would save France, Baudricourt still sceptical but assured by his parish priest “that the devil was not in her” finally gave in and provided her with an armed escort of a few men.

It is dressed as a man and with her hair cut that Jeanne finally left Vaucouleurs in February 1429.

The group travelled without problem through France and thanks to Baudricourt's letter of introduction, Jeanne was permitted to meet the dauphin at his court in Chinon. She had never seen Charles before, and yet legend has it that she recognised him immediately, hidden among his courtiers, while a subject had taken his place in the room. Jeanne presented herself as Jeanne la Pucelle and told him that the “Lord of the skies” had ordered her to take him to Reims in order to be crowned. She addressed him as Dauphin and not as King stressing thus the fact that only a coronation could make him a king by divine right. Jeanne and Charles talked in secret, nobody knows what they said to each other, but it is reported that the king came out with an enlightened face.

Although convinced, Charles had however the prudence to test Jeanne. He had ladies of the court confirm her virginity and ordered her to be examined by theologians in Poitiers. They recognised in her “humility, virginity, devotion, honesty and simplicity” but advised the king to ask her for a sign proving that she actually spoke in the name of God. Jeanne replied by asserting that such a sign would be the lifting of the siege of Orléans which she had prophesied.

After a final check of her credentials in Domrémy, Charles VII gave her an armour, a guard of a few men, and allowed her to join a supply convoy on its way to relieve Orleans. The legend has it that none of her companions dared to oppose her and that they obeyed her heartedly: the men no longer swore and said nothing when in Blois she sent away the prostitutes who accompanied the convoy.

The convoy arrived in Orléans on 29 April 1429, delivered the supplies and Jeanne met Jean d'Orléans, the future Count of Dunois, commander of the armed forces in Orléans. She was greeted enthusiastically by the population, but the war captains were reserved. However, with her faith, confidence and enthusiasm, she managed to infuse the desperate French soldiers with new energy and to force the English to lift the siege of the city on the night of 7 to 8 May 1429, earning herself her nickname of the Pucelle of Orléans.

After the victory of Orléans, the French had two possibilities: attack Paris or hurry to Reims to crown the king, which Jeanne wanted above all. The dauphin, hesitating, ended up agreeing with Jeanne although the gamble was risky as Reims was surrounded by English and Burgundian possessions. A decisive battle took place in Patay, against the English led by John Talbot, who had just been driven out of Orleans. Everyone had still memories of the massacre of Agincourt but Jeanne enthused the army and promised the victory in the name of God. The battle ended with 2,000 dead on the English side and John Talbot prisoner of the French whose losses were almost nil. On their way to Reims, the French liberated Auxerre, Troyes and Chalons and the dauphin could finally make his entrance into the cathedral of Reims on 17 July 1429 to receive the sacrament from the Holy Ampulla with Jeanne at his side, carrying his standard. The English regent, the Duke of Bedford, reacted immediately and had the young Henri VI crowned at Notre-Dame de Paris but, without the Holy Ampulla essential to validate the ritual, this coronation was meaningless.

There was now only one king left in France, the heir of the Valois, Charles VII. Jeanne's mission was crowned with success, and in a few months, victory had changed sides.

The capture of Jeanne d'Arc

After the coronation, Jeanne tried to convince the king to take back Paris from the Burgundian and the English, but he was hesitating. They eventually arrived in Saint-Denis from where they started an attack on Paris at the gate Saint-Honoré on 8 September 1429. Wounded in the thigh during the assault Jeanne nevertheless resumed the fight, but the miracle of Orléans did not repeat itself. The king faced with a lack of money and food chose the path of negotiation with the duke of Burgundy and finally ordered to lift the siege and dissolve the army. Jeanne went on fighting all the same but from then on she led her own troops as an independent warlord, she no longer represented the king.

After the coronation, Jeanne tried to convince the king to take back Paris from the Burgundian and the English, but he was hesitating. They eventually arrived in Saint-Denis from where they started an attack on Paris at the gate Saint-Honoré on 8 September 1429. Wounded in the thigh during the assault Jeanne nevertheless resumed the fight, but the miracle of Orléans did not repeat itself. The king faced with a lack of money and food chose the path of negotiation with the duke of Burgundy and finally ordered to lift the siege and dissolve the army. Jeanne went on fighting all the same but from then on she led her own troops as an independent warlord, she no longer represented the king.

She rejoined the royal army in October 1429 at the siege of Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier which fell on 4 November 1429. This was followed by the unsuccessful siege of La Charité-sur-Loire in December which had to be abandoned after a month.

She rejoined the royal army in October 1429 at the siege of Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier which fell on 4 November 1429. This was followed by the unsuccessful siege of La Charité-sur-Loire in December which had to be abandoned after a month.

At the beginning of 1430 Jeanne was invited to join the court at the Château de La Trémoille in Sully-sur-Loire. By that time, the intentions of the duke of Burgundy had become clear: alongside the English, he wanted to take back the cities that had passed to the king. But Charles VII had no longer an army and he left Jeanne to fend for herself, a surprising attitude to say the least towards the very same person who had made him king. At the head of a company of volunteers she made her way to Compiègne besieged by the Burgundian. She was acclaimed in Melun on Easter day where she waited in vain for the king's reinforcements which never materialised. She continued nevertheless and once in Compiègne, multiplied her sorties against the enemy. The sortie of 23 May 1430 proved fatal: having strayed too far away she faced a sudden Burgundian counter-attack led by John of Luxembourg. She ordered the retreat and remained in the rearguard to fight to the last, just to find the drawbridge of Compiègne raised when she finally made it to the city. Betrayal or recklessness? Either way, Jeanne was unhorsed by an archer in close combat and captured by John of Luxembourg. Brought to the castle of Beaulieu, around 35 km north of Compiègne, she tried to escape for the first time. Beaulieu being too near of the battle zone, it was decided to transfer her to the castle of Beaurevoir, 60 km further north. Once there she tried again to escape but got seriously injured when she jumped out of a window.

John of Luxembourg was not keen on keeping such a difficult captive, so he eventually sold her to the English on 21 November 1430 for ten thousand pounds and entrusted her to Pierre Cauchon, bishop of Beauvais and ally of the English who brought her to Rouen a town firmly controlled by the English.

The trial of Jeanne d'Arc

The preliminary investigation began in January 1431. Despite long interrogations the investigators, led by the bishop of Beauvais Pierre Cauchon, were unable to establish a valid charge and settled by default on the facts that she was wearing men's clothing, had left her parents without their permission, and above all on the fact that she systematically relied and appealed on God's judgement rather than the one of the established Church. They also considered that the “voices”, to which she constantly referred were in fact inspired by the devil and finally came up with seventy charges, the main one being “revelationum et apparitionum divinorum mendosa confictrix” meaning falsely imagining divine revelations and apparitions.

Deliberations started on 5 April: around one hundred and twenty people took part, canons and abbots, doctors of theology and ten delegates from the University of Paris, all carefully selected. Several of them testified during the rehabilitation trial which took place after Jeanne's death in 1450 about their fear of reprisals if they had refused to comply to the will of the English.

Deliberations started on 5 April: around one hundred and twenty people took part, canons and abbots, doctors of theology and ten delegates from the University of Paris, all carefully selected. Several of them testified during the rehabilitation trial which took place after Jeanne's death in 1450 about their fear of reprisals if they had refused to comply to the will of the English.

While she waited for her judgement, Cauchon endeavoured to persuade Jeanne to acknowledge her wrongs and do penance, using in turn gentleness, authoritarian warnings and terror. She was even threatened with torture on May 9 and brought before the executioner and his instruments: without any more success.

While she waited for her judgement, Cauchon endeavoured to persuade Jeanne to acknowledge her wrongs and do penance, using in turn gentleness, authoritarian warnings and terror. She was even threatened with torture on May 9 and brought before the executioner and his instruments: without any more success.

The verdict came at last:

- The doctors of the University of Paris Sorbonne concluded that Jeanne was guilty of being schismatic, apostate, a liar, soothsayer, suspect of heresy, misguided in her faith and a blasphemer of God and the saints.

- As for the masters of canon law, they went further: for them, Jeanne was certainly a heretic and should be punished as such if she did not repent.

This was read to Jeanne, followed by a “charitable exhortation” to recant. She declared that she preferred death. However, as she saw the pyre erected for her on the next morning, she gave in when the bishop Cauchon proclaimed the final sentence: she declared to be ready to defer to the authority of the Church. She was read an abjuration, in which she acknowledged that her voices and apparitions were not to be believed and promised to renounce her errors. Cauchon then condemned her to life imprisonment - a sentence that could be modified if she behaved well - as was customary in such cases. Jeanne was taken back to her prison, where she agreed for the first time to return to wearing women's clothes.

Four days later, however, the judges who visited her found her dressed as a man again. Worse: when they asked her if she still believed “in the illusions of her alleged revelations”, she told them that her voices had reproached her for her “betrayal” on the very night of her return to prison. Cauchon had no difficulty in convincing her assessors that the relapse into heresy was undeniable.

In the morning of 30 May 1431, during a new public ceremony, this time held in the Place du Vieux-Marché, Jeanne was condemned as a “heretic relapse” and, according to the usual formula, “delivered to the secular arm”, that is to say, to the English, who immediately burnt her alive.

Her ashes were thrown into the Seine, to prevent them from being recovered and venerated as relics by possible partisans.

Twenty years later, when he had reconquered Normandy and thrown the English out of France, Charles VII saw to it that Jeanne's trial was annulled in due form with the Pope's consent. For with the condemnation of Jeanne d'Arc, it was the divine character of the king of France whose champion she had been, that had been denied.

Want to read more? Go on to Our Favourite French Recipes or go up to Background

$ updated from: Background.htxt Mon 28 Apr 2025 14:55:37 trvl2 — Copyright © 2025 Vero and Thomas Lauer unless otherwise stated | All rights reserved $